It is hypothesized that dark matter, which cannot be directly seen, accounts for a great amount of the total mass of our universe. Its existence is inferred from the gravitational effects it appears to have on everything else. One could imagine, therefore, that dark matter is in fact responsible for configuring the relationships of all things to one another, binding person to person, people to place and present to past. When I think of the focus of Deanna Bowen’s artistic gaze, I imagine a kind of dark matter. Her practice concerns itself with histories of Black experience in Canada and the US—often connected directly to her own family—that remain below the threshold of visibility, not because they are impossible to see but because they are difficult for the majority culture to acknowledge. Mining overlooked archives and forgotten documents, Bowen makes use of a repertoire of artistic gestures to bring traces of a complex, deeply personal and often violent past into public visibility.

Bowen’s solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery, A Harlem Nocturne, comprises two separate trajectories of research that follow the artist’s maternal lineage in Canada. In one gallery, a four-channel video installation presents footage from On Trial The Long Doorway (2017), a project co-commissioned by CAG and Mercer Union, Toronto. It focuses on a lost 1956 CBC teledrama titled The Long Doorway, in which Bowen’s great uncle Herman Risby played a supporting role. It tells the story of a Black legal aid lawyer tasked with representing a white University of Toronto student charged with violently assaulting a rising Black basketball player. The Long Doorway is potent for Bowen because Canadian culture so infrequently, in her words, “takes up questions of race in its own place” and because the issues the episode examined in the mid 1950s are no less urgent today. Conspicuously, no recordings of the teledrama exist, so Bowen used the recovered script and set design notes to experimentally re-stage the work with five Black actors, each of whom performed multiple roles throughout the exhibition’s public, video-recorded rehearsals. Just as the original script refuses any resolution to the tense questions it poses around race and class, visitors to Bowen’s multi-channel video installation at CAG are confronted with an amalgam of overlapping readings of the script, and we must follow the cast through myriad threads of dialogue as they parse out the scenes and deconstruct them from their own positions. Off-site at the Western Front, a single edited cut presents Bowen’s re-staged teledrama in its entirety.

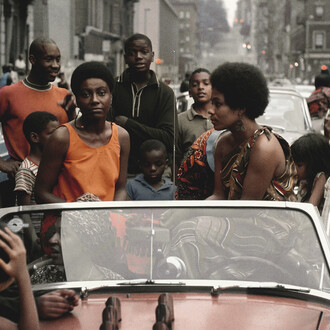

Across the hall in CAG’s larger gallery, a second major suite of works presents a terrain of research that Bowen undertook in Vancouver in 2017–18, recovered from civic documents, newspaper clippings and numerous personal and organizational archives. This material traces a series of interconnected figures who formed an integral part of Vancouver’s Black entertainment community from the 1940s through the end of the 1970s. It includes Herman Risby, who performed in numerous Vancouver theatrical productions; renowned dancer, singer, songwriter and choreographer Leonard Gibson (who shared the stage with Risby in Vancouver’s Theatre Under the Stars 1952 production of Finian’s Rainbow); internationally recognized American choreographer, dancer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, who performed with her company in Vancouver in 1947 (Gibson joined the company on stage as a last minute replacement and was then offered a scholarship by Dunham to study at her school in New York); Vancouver-based jazz vocalist Eleanor Collins, who appeared with Risby and Gibson in Finian’s Rainbow and was the first Black artist in North America to host her own television program, the CBC variety series The Eleanor Show (1955) (for which Gibson served as choreographer); Bowen’s first cousin once removed, Choo Choo Williams, a shake dancer (who took dance lessons from Gibson) and co-owner, along with her husband Ernie King, of the Harlem Nocturne nightclub at 343 East Hastings Street, from its establishment in 1957 until its sale in 1968. As Black bodies living and working in a settler colony rife with societal and institutionalized police racism, they were at once invisible and hypervisible, variously admired, embraced, exoticized, surveilled, discriminated against and violently attacked. They enjoyed certain celebrity in their local milieu and endured differing degrees of prejudice, bigotry and segregation. What these recovered documents ultimately reveal is the picture of a complex, varied and intersectional Black community in Vancouver, one offering a powerful counterpoint to common narratives that oversimplify the city’s Black presence by containing it within the spatial, economic and temporal confines of Hogan’s Alley.

We encounter these figures in the exhibition by navigating a field of archival evidence—evidence being precisely that which is not self-evident and becomes evident only through the eyes and ears of others. Bowen is careful to preserve what the theorist Allan Sekula calls the “radical antagonism” of the documents’ different modes of pictorial address (the structures of power underlying grainy newspaper images and FBI files differ vastly from those of promotional headshots, televised dance numbers and family photographs). She translates each document into a discrete form, in an explicit effort to bring them into visibility. We regard choreographic notation, reinterpreted and re-performed dance sequences, large-scale wall vinyl, framed prints, photocopied transparencies, hand-painted signs, sculpture, a book work and, off-site elsewhere in the city, a billboard. Everywhere we are confronted by Bowen’s tools of retrieval and viewing, whether overhead projectors, lightboxes or flatbed film editors; in fact these apparatuses are often the only means through which the material becomes visible and legible. Such legibility, however, is simultaneously challenged by the many registers of blackness that comprise A Harlem Nocturne: a darkly luminous black in the lightbox and video works; a light-absorbing black flocking; draped black chiffon and black redaction. These different modalities of black speak not only to the obstructions and opacity Bowen encountered in her research efforts, but also to her strategies for protecting communities close to her family by avoiding a repetition of the overexposure they endured in their public and private lives.

A Harlem Nocturne takes up many of the concerns currently shaping discussions in photography and Black visual studies. Africana studies scholar Tina M. Campt urges her readers to consider photographs as dynamic and contested sites of Black cultural formation and as “an everyday strategy of affirmation and a confrontational practice of visibility.” She follows feminist theorist and photography historian Laura Wexler in stressing that “what we learn of the past by looking at photographic records is not ‘the way things were.’ What they show us of the past is instead a ‘record of choices.’” Campt extends this to suggest that photographs offer a record of intentions as well, as “it is only through understanding the choices that have been made between alternatives—learning what won out and what was lost, how it happened and at what cost—that the meaning of the past can appear.”

Bowen’s work also reminds us of photography’s power to categorize and contain. As Sekula contends, to achieve legitimacy photography relied heavily on the archival model. “We might even argue,” he suggests, “that archival ambitions and procedures are intrinsic to photographic practice.” In his influential 1986 essay “The Body and the Archive,” Sekula describes the way that, “in a more general, dispersed fashion . . . photography welded the honorific and repressive functions together.” He continues:

“We can speak then of a generalized, inclusive archive, a shadow archive that encompasses an entire social terrain while positioning individuals within that terrain. . . . The general, all-inclusive archive necessarily contains both the traces of the visible bodies of heroes, leaders, moral exemplars, celebrities and those of the poor, the diseased, the insane, the criminal, the nonwhite, the female and all other embodiments of the unworthy.”

Perhaps this “shadow archive” is ultimately Bowen’s dark matter—a system of representation that cannot be seen directly but silently constitutes the all-encompassing structure within which Black experience was contained, made visible and variously vilified or admired in twentieth century Vancouver (as elsewhere). In daylighting its evidence, Bowen’s objectives are forensic. She understands how to search for these traces, because she too inhabits a body that is subject to this same system’s principles of organization. And therein also lies the force of her work, her visual and material mattering of that archive—both its residual and potential meanings—because, to borrow the words of artist Hito Steyerl, “a document on its own—even if it provides perfect and irrefutable proof—doesn’t mean anything. If there is no one willing to back the claim, prosecute the deed, or simply pay attention, there is no point in its existence.”

Presented in partnership with Capture Photography Festival. On Trial The Long Doorway was commissioned and produced through a partnership between the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver and Mercer Union, a centre for contemporary art, Toronto. Production support was provided though a Media Arts residency at the Western Front, Vancouver. Additional support provided by Clark’s Audio Visual.