A human being should never stop thinking. It is the only shield against barbarism. Action and words are the two conveyors of freedom. If he stops to think, every human being can act as a barbarian.

(Hannah Arendt : The banality of evil.)

It was on April 16, 2017. In Marseille.

Sitting facing the sea, enjoying the last rays of sunshine of the day, I was procrastinating and dithering on wether or not I would go "all the way up" to the Friche Belle de Mai to discover the exhibition Antoine de Galbert and Paula Aisemberg had urged me to see. It is therefore with a sense of obligation that I started walking towards the exhibition, convinced I would « be done » in 20 minutes and that my visit would confirm my rather mixed first impression, an opinion based on images I’d seen on the web.

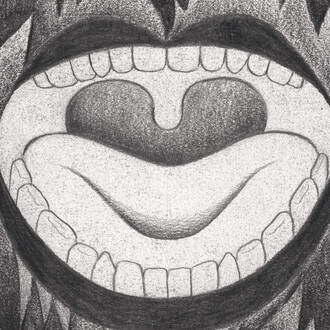

I came out an hour and twenty minutes later, wiped out and overwhelmed. Whipped out by the « the story » of course, of this young Roma girl who, after hiding out with her family, was arrested at the age of ten and sent off to Nazi concentration camps (Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and finally Bergen-Belsen), surviving them, and who then decided, 45 years later, to convey to the world the testimony of the Roma genocide (on the 700 000 European Gypsies, between 300 and 500 000 perished). And overwhelmed as well because I was facing an œuvre, a multi-cut diamant altogether black, eerie, sad, dreadful and at the same sublime, filled with hope and radiant.

Therefore, coming out of the show (thanks should be given to its curator Xavier Marchand), my doubts regarding wether or not I should represent Ceija Stojka’s work were still there, only they had shifted. Convinced as I was of the extraordinary nature of the work, I was reflecting upon the pertinence and more precisely « the right » to introduce drawings, gouaches, paintings in an art gallery and then turn them into a « matter of trade ». Beyond the fact that Ceija herself sold some of her works while she was alive, how should I conceive my role if, in agreement with her son Hodja and her daughter in law Nuna, I decided to show her work at the gallery ? What am I allowed to say ? What am I not allowed to do ? What must I say ? What must I do ? It is in this continuous back and forth between right on one side and duty or obligation on the other that I spent the following two weeks reflecting.

The notion of duty takes precedence over that of right which is subordinated and relative to it, Simone Weil wrote. A right has no efficiency in itself but only in regards to the duty it refers to… This duty is eternal. It answers to the eternal destiny of mankind.

To have an art gallery is to believe we have a responsibility and an influence (however small) on the world that surrounds us, that we act as passers-on. To be the gallerist of Ceija Stojka’s work is to say that we too can try to carry on this message she fought to convey. A dreadful and unbearable testimony but also the account of an incredible power of resilience. As if, through her work, the art of Kintsugi was reborn, this traditional Japanese art that consists in putting back together a broken object by highlighting its scars with gold instead of hiding them.

To see Ceija’s work is to experience (in relative terms of course) the undertaking of the destruction of men by men, the horror of the world. An experience lived through the eyes of the child she was and miraculously remained when she decided to paint and draw the unthinkable.

For even words, undoubtedly, weren’t enough.

Ceija Stojka was born in Austria in 1933, the fifth child out of six in a family of Roma horse merchants. Deported at the age of ten with her mother Sidonie and other members of her family, she survived to three concentration camps, Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen.

It is only forty-five years later, in 1988, at the age of fifty-five, that she felt the need and the necessity of speaking about it ; it is the start of an incredible memory work and, even-though considered as illiterate, she writes several poignant books, in a very poetic and personal style, which will make her the first Roma female survivor to account for her experience in the Nazi death camps, against oblivion and denial, against endemic racism.

Her testimony doesn’t end with the texts she will publish (4 books in total between 1988 and 2005), which very quickly award her a role as a pro-Roma activist in the Austrian society. In the 1990’s she starts to paint and draw, while in this field too, she is self-taught. She devotes herself to it body and soul, until her death in 2013. Her body of work, paintings and drawings, created over about 20 years, on paper, cardboard or canvas, reckons about one thousand works. She was exhibited in Germany, Austria, and recently at La Friche Belle de Mai, Marseille and La maison rouge, Paris.

![Mohsin Taasha Tappa-e Shuhada Roshnaaie [Hill of martyrs of enlightenment] from Rebirth of the Reds series, 2022. Courtesy of Galerie Eric Mouchet](http://media.meer.com/attachments/88a9b99d56257bd44c1e6e68377f280e3350a066/store/fill/330/330/e9d8f49d377be692a716e38249550040d715c57af996eabbdb47f1967679/Mohsin-Taasha-Tappa-e-Shuhada-Roshnaaie-Hill-of-martyrs-of-enlightenment-from-Rebirth-of-the.jpg)