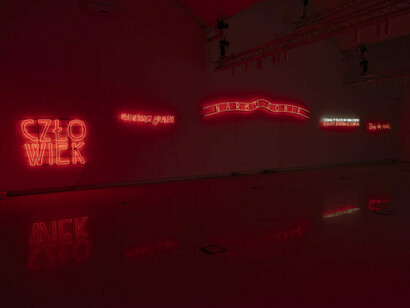

Hubert Czerepok’s exhibition creates a space in which neon texts, light, media, and cultural quotations become entangled in the mechanisms of displacement, denial, and repetition. Sigmund Freud had already identified these mechanisms as symptomatic “acts of getting lost” in speech and action, such as slips of the tongue and mistakes. It is well worth approaching this exhibition as a reflection on the unconscious – on what can emerge in the space between language and its form, between a symbolic message and its unconscious, excluded aspect. Czerepok often employs neon signs that feature texts from the media, popular culture, history, and public space. He is interested in anything that can serve as a slogan, manifesto, or expression of hate speech (e.g., You will never be a Pole). The artist also borrows quotes from literature, including passages from the books of Jan Tomasz Gross. Czerepok’s works operate on a certain unconscious, dislodged layer of our collective language and culture. What is – seemingly openly – expressed by the neon sign points to a layer that has been “taken over,” “confused,” or “suspended.” Here, one can draw an analogy with Freud’s concept of “slips of the tongue.” The act of language (or action) says more than meets the eye. One neon sign project by Czerepok, for instance, subtly manipulates language by inserting the word “not” where it wasn’t previously present: “One day people will not live like brothers.” This small, “corrected” neon sign reflects a shift that points not only to history but also to the replication of a mistake: humanity does not learn; it repeats what it was meant to overcome. This could be read as a collective “mistake”/”slip of the tongue”: an idealistic vision has been squandered, and the neon sign, through a slip of the tongue, exposes this very fact. Another category of Czerepok’s neon signs comprises “malfunctions.” These pieces draw inspiration from instances in which a neon sign’s content is subversively altered by the burning out or flickering of one of its letters. A 1980s urban legend states that when the ideologically appropriate neon sign promoting Poznań’s Osiedle rusa (rusa housing estate) malfunctioned, it read instead – much to the chagrin of the authorities – Osiedle USA (USA housing estate).

In The psychopathology of everyday life, Freud described slips of the tongue, pen, and action as “failed acts” that are nevertheless unconsciously “successful” because they reveal a repressed or hidden desire, conflict, or impulse. In light of Freud’s theory, Czerepok’s neon signs can be read as an assortment of “cultural slips of the tongue” in which the text-slogan is modified to draw attention to what has been left out, repressed, or repeated. They can therefore be read not only as an endorsement of the message but also as a detector of an unconscious shift in the language of culture.

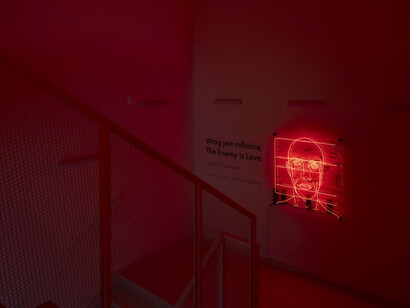

By examining the works of Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who was influenced by Freud and Lacan, we can discern that what appears in Czerepok’s neons to be merely a decoration of light and word is something more fundamental, becoming an ideological symptom. In Žižek’s view, ideology is not simply a distortion of reality but the very condition of its potential: reality could not be sustained without prior ideological mystification. In this context, Czerepok’s neon signs – text-objects suspended between public space and art – can be seen as revealing the structure of fantasy that sustains the symbolic form of the existing social and linguistic order. The titular neon sign, The Enemy is Love, does not reproduce the slogan of hatred but rather reverses it, subjecting it to irony and emptiness. It can be seen as an example of a “Freudian slip.” This confession – which would perhaps sound irrational in public space – is communicated in the art gallery as a symptom: a social event of language that says something about what we do not say openly. This seemingly meaningless message reveals a hidden, perverse desire for reconciliation or betrayal.

Czerepok’s exhibition functions as an arrangement of symbolic, rather than artistic, slips: shifts, twists, and repetitions reveal what the socio-cultural system attempts to suppress. Neon signs do not communicate a clear message but reveal the unconscious structures of language and ideology. Czerepok is from the generation that can still remember neon signs in the cities of communist Poland. Despite their apparent advertising purpose, they served primarily as decorative and persuasive elements. Ingenious in form, they often acted as an unattainable model of a seductive combination of light, language, and ideology. All the more so today, under the guise of “normal” linguistic communication – in this case, the attractive form of a neon sign – a structure of fantasy plays out: we believe that it is merely a decoration, a slogan, or light, and yet it is a manifestation of something different. With his work, Czerepok draws out this other element, “something different” that demands reflection: what does the space of a public slogan conceal? What desires, what violent exclusions are reproduced here? A mistake, a slip – that is, the displacement of part of a neon sign – becomes a space for critical reflection.

In this context, one can also refer to the idea of “repetition” in both the Freudian and Žižkovian sense (repeated phantasm, recurring ideology). Czerepok points out that history, visual slogans, and neon signs repeat themselves, return, and are reproduced within the social realm. The artist propels the viewers into this spiral not to remind them, but to enable them to identify the mechanism of repetition and its structure. Czerepok’s neon signs are not simply texts but also visual messages drawn with light. The exhibited works depict sections of boundary lines, including the Israel-Gaza Strip, Poland-Belarus, and USA-Mexico borders. These are lines of division marked by conflict and suffering. Their minimalist, decorative aesthetics clash with the tragedies that unfold along these borders.

Hubert Czerepok’s exhibition would appear to strive for a moment of awareness: not for the rejection of neon signs as a form, but for neon-text-light to move past being merely a decorative “gadget” and turn into a question. Looking at Czerepok’s neon signs, the viewer becomes a witness not only to light but also to the unconscious movement and shifts in language and ideology. One’s own perception may then turn into a Freudian slip – we think we understand, but the neon signs suggest that perhaps what we understand is a shift and that maybe what we overlook is the most significant.