Every year brings its own wave of prestige dramas, buzzy comedies, and cult oddities that ignite group chats for weeks. But 2025 was unusually strong, not just for returning seasons, but for brand-new shows—projects unburdened by pre-existing fandoms or decade-long lore. Fresh, new ideas that remind you why people continue watching long-form content even as it finds itself in a rapidly shrinking ecosystem.

Maybe it’s the post-strike recalibration, maybe creators are pushing harder for bold first impressions, or maybe studios have finally learned that audiences respond to personality over algorithms. Whatever the reason, this year’s debuts are sharp, confident, and strangely unified in their diverse ambitions. Inventive cinematography, formal gambits that feel motivated, episodic, and seasonal arcs. Across genres, there’s a palpable desire to push television back towards something tactile and lived-in, while also continuing to broaden its horizons.

What’s especially exciting is the range: a medical thriller with the pulse of a single continuous shift; a coming-of-age mini-series shot with the rigor of art-house cinema; a Hollywood satire that’s both breezy and barbed; an existential horror-comedy that might be the defining show of the moment, and a towering piece of prestige storytelling from one of TV’s most iconic writers. Taken together, these five shows don’t just represent the best of 2025—they’re early signs of what the next era of television could look like: specific, creator-driven, and fundamentally unwilling to settle.

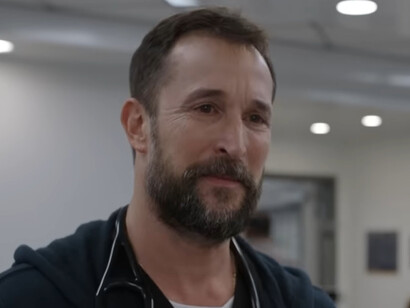

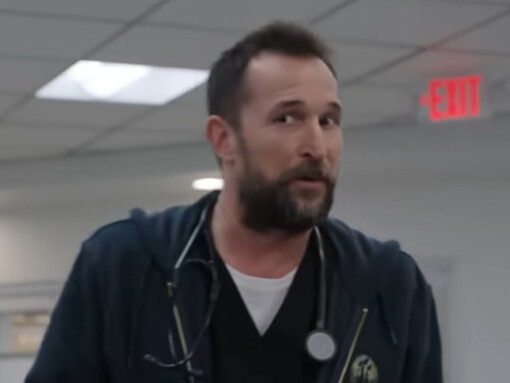

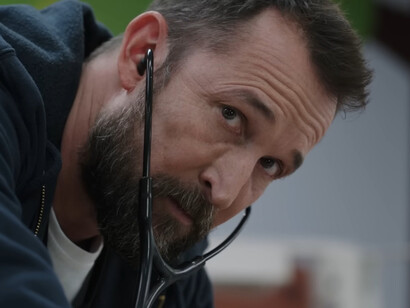

The Pitt

I don’t usually gravitate toward medical dramas. The monotonous rhythms of Grey’s Anatomy, House, or E.R.—urgent monologues, earnest melodrama—have never really been my cup of tea. Although the setting is meticulously realized and accurately researched, The Pitt isn’t quite a medical drama in the conventional sense. It’s more of a pressure-cooker thriller disguised as one: a season composed of a single, unbroken hospital shift, with each episode representing one real-time hour. It’s a structural experiment that could easily feel like a gimmick, but instead it becomes the engine of the show’s momentum. Everything is on edge; no one can breathe. Time itself is a constant antagonist slowly ticking away at our beloved characters.

What makes it even more compelling is how it uses this format to carefully reveal its ensemble. We don’t get lengthy backstories delivered through forced exposition; we learn who these people are by watching how they operate, how they improvise, how they choke, and how they care. Every strength is tested, every flaw exposed. The high-stakes environment doesn’t just serve to manufacture tension—it forces truths, some harder than others.

The show’s pacing is relentless without feeling chaotic, because the emotional throughline is always clear. Every moment of action is anchored by a clear human cost, whether that’s the toll on the patients or the staff who are barely keeping it together. What emerges is a surprisingly intimate portrait of people who rarely have the luxury of introspection until their shift is over—if it ever is. For a genre often dominated by formula, The Pitt feels refreshingly alive.

Adolescence

When Hideo Kojima calls something the best show of the year, you know you’re in for something special. Stephen Graham’s blistering mini-series really is operating on a whole other level. What could have easily been a lurid true-crime riff becomes a meticulous character study in guilt, violence, and the terrifying blankness of youth under pressure.

It finds a formal signature in its use of long takes, but not the stylish, balletic kind seen in prestige thrillers. These are suffocating, punishing shots that refuse to let the viewer look away from the raw emotional fallout. Scenes stretch past the point of comfort, placing us directly inside the spiraling panic of a child who has done something irreversible and barely understands the magnitude of it. That’s where Owen Cooper’s star-making performance comes in. He plays the boy with a terrifying interiority: withdrawn, observant, and unnervingly calm, as though pieces of him are shutting down in real time.

The adults around him—teachers, parents, police—aren’t framed as authority figures so much as bewildered participants in a tragedy they can’t fully process. The show is less interested in the mechanics of the crime than in the psychological void left behind, a vacuum that pulls everyone inward. That frightening age where a child’s inner world becomes impossible to comprehend until it’s far too late.

The Studio

But this year wasn’t all drama and tragedy: from the duo behind Superbad comes a backstage farce drenched in sun-soaked Hollywood cynicism. Seth Rogen stumbling through glass offices and elegant sets as though gravity itself personally has it out for him. But behind the laugh-out-loud slapstick is a surprisingly sharp satire of an industry too busy chasing synergy to notice it’s literally tripping over its own shoelaces.

This series also makes extensive use of long takes—not in the same meticulous, reverent way as Adolescence, but in a deliberately breezy, almost improvisational way. These sequences give a similar manic energy to Birdman, but without all the self-importance; here, the camera isn’t gliding—it’s hustling to keep up. The result is visually impressive but tonally light, making space for both sharp cinematic commentary and punchline-driven chaos.

What elevates The Studio above similar shows is its deep understanding of modern Hollywood. A place where every decision is a compromise and every compromise leads to someone’s payday. Celebrity cameos appear with giddy regularity, but they serve the satire rather than overshadow it. The colour palette is warm and inviting, the locations are impossibly expensive, and the show isn’t shy about flaunting its aesthetic pleasures—because part of the joke is how good the artifice looks even when everything beneath it is crumbling. A rare show that effortlessly entertains while quietly saying something real. It’s a comedy first and foremost, but one with teeth. A love letter to cinema, as well as a suicide note for the Hollywood system.

The Chair Company

Shortly after the release of their feature film Friendship, Tim Robinson doubles down with director Andrew DeYoung to craft something stranger, darker, and even more eerily incisive. The Chair Company begins with an almost laughably mundane incident: a man, living a thoroughly normal life—secure job, loving wife, two happy kids—becomes obsessed with the manufacturer of a chair that breaks beneath him, humiliating him in front of his peers. From that seed sprouts a suffocating spiral into modern paranoia, corporate conspiracy, and existential dread.

Robinson’s performance is frankly astonishing. Though he’s playing his usual persona, the eight episodes really give him space to run with it. More subdued than his usual off-kilter mania but still unnervingly precise in that uneasy space between bewilderment and open rage. He’s always excelled at using awkwardness as a weapon, but here he pushes into something more psychological, only slightly off, like a frequency only dogs can hear. The show often feels Lynchian, not because it imitates Lynch’s imagery, but because it shares his gift for making an ordinary situation feel terrifying in a way you just can’t quite put your finger on. Every conversation feels one nudge from collapsing; every character appears normal until they suddenly aren’t.

A razor-sharp satire, taking aim at modern digital life—smartphones, data harvesting, corporate doublespeak—but it never slips into didacticism. Instead, the comedy emerges naturally from the world we already inhabit. The deeper our protagonist digs, the more it mirrors our own escalating anxieties as we struggle to make sense of a society that no longer explains itself. By its finale, the series has mutated into something more akin to surreal horror, while still retaining the strange, bitter humor throughout. It’s not easy television—a lot of real toe-curling stuff, some scenes could even be considered nightmare-inducing—but it’s the only show that feels perfectly calibrated to our current cultural climate.

Pluribus

Every so often, a creator returns with a project that feels like the culmination of everything they’ve achieved, and it instantly becomes a classic. With Pluribus, Vince Gilligan delivers just that—a series that fuses the immaculate visual language of Better Call Saul with the propulsive storytelling of Breaking Bad. A show that feels a little familiar and yet entirely new, arguably the strongest work of his career.

Rhea Seehorn finally receives the spotlight she’s long deserved, anchoring the series with a performance of precision, intelligence, and quiet ferocity. Her character is written with the depth and unpredictability Gilligan reserves for his protagonists—the kind who make even their smallest decisions absolutely seismic. Every episode seems to subtly shift the show’s scope, expanding outward just enough to destabilize the viewer. You never quite know where the narrative is heading, or what the show wants you to believe.

What’s most impressive is how Pluribus manages its tone. It’s tense without being suffocating, stylish without being showy, and emotionally rich without ever pandering. Gilligan trusts the audience, laying out moral clues and visual motifs that accumulate into something breathtakingly profound. There’s a confidence to the filmmaking—the compositions, the pacing, the way scenes move—that reminds you just how rare it is to see this level of craft on television.

Calling it the best season of TV this year almost feels like an understatement. Pluribus isn’t just a standout among new shows; it’s a landmark achievement for modern serialized storytelling. I think it’s safe to say the medium is in very good hands.