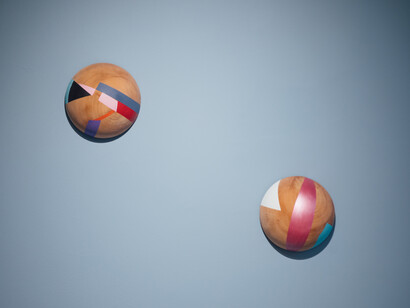

In this exhibition, Henry Salazar imagines a possible city: a metropolis inside Policroma's project room, where the promises of modernism blend with the rhythms, colors, and materials of the Colombian Pacific. The sculptures are arranged like a walk-through model: towers, spheres, ovals, and cylinders of turned wood that recall the languages of Brancusi or Henry Moore, but filtered through the climate, humidity, and tropical inventiveness. What might seem like a reference to the Western sculptural canon is transformed here into something else: an affective and situated reinterpretation, a handmade modernity.

The pieces were made in collaboration with woodturners from Tumaco, a craft that is currently experiencing a renaissance thanks to local trade schools. The wood comes from industrial waste from plywood factories: discarded cedar and oak rollers, which the artist recovers and transforms. This gesture—turning what was going to be firewood into sculpture—is not an attempt at environmental correction, but rather an ethic of reuse and permanence. Salazar works with what is left, with materials that still retain the memory of their origin and can be touched, turned, and inhabited once again.

In this project, he revisits the history of modern architecture in Tumaco, a city that, after the fire of 1947, was redesigned according to the ideals of Le Corbusier. Those houses, designed according to European plans, ignored the conditions of the tropics.

Salazar's sculptures encapsulate this disconnect: water towers, antennas, and housing structures transformed into organic, colorful volumes. The palette—intense yellows, blues, and reds—echoes the colors used by the inhabitants of Tumaco to paint their stilt houses, extending the chromatic pulse of the territory into art. Beside them, the cyanotypes evoke the blueprints with which architects reproduced their plans, but here they record the houses that survived abandonment: just seven of the 1,200 that once embodied the dream of modernization.

Acclimatized tropical modernism proposes a fresh look at these tensions between the imported and the indigenous, between utopia and adaptation. In Salazar's hands, wood, color, and scale become tools of reconciliation: it is not a question of denying modernity, but of translating it into climate, body, and memory. In this model city, each form is a testimony to resistance, a sensitive architecture that, rather than erecting monuments, seeks to reinvent the idea of inhabiting.

(Text by Paula Builes)