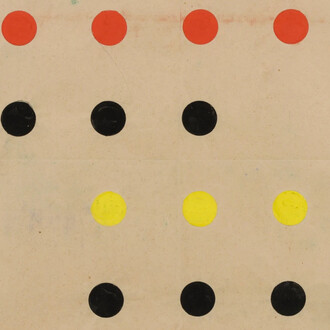

Vito Schnabel Gallery is pleased to announce the opening of Fits and starts on October 29 in New York, an exhibition of new works by Robert Storr. Painted over the last year, Storr’s striking geometric compositions are contemplative and powerful. Storr follows his own intuitive rules when creating each piece, beginning the process by creating a drawing on his iPhone and blocking out areas of color. This digital study serves as the sketch for the final painting, which allows him to experiment with form and color before committing to the canvas.

As Gestalt psychologist Rudolf Arnheim argued, the mind tries to "correct" visual anomalies in the interest of holistic pictorial phenomena. Accordingly, symmetry and asymmetry, balance and imbalance, and the spatial tension they set in motion are central dynamics in Storr’s work. The forms in each picture engage in a quiet but persistent dialogue; a weight on one side of the canvas calls for compensation elsewhere. There is constantly a push and pull, fullness and absence. Mirrored elements appear but are never exact, creating a sense of dissonant harmony. Each piece harbors a precarious feeling, a delicate imbalance with the illusion of symmetry. But as Storr notes, “It is not there to reassure you. It is there to make you wonder.”

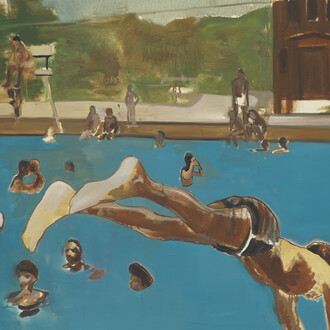

Storr draws inspiration from music, dancing, and of course, art. He cites, in particular, a print from Francisco Goya’s La Tauromaquia, a series of 33 etchings from 1815-16 depicting bullfighting in Spain, as a pivotal influence. In Goya’s image, the right half of the work is dense with figures in chaotic motion, capturing the moment that the mayor of Torrejón is impaled by the fearsome bull. The left side remains sparse, marked only by the head of a single onlooker emerging from behind a barrier. The stark spatial contrast in Goya’s composition strongly informed Storr’s use of visual opposition and asymmetry.

Through his work as a painter, curator, art critic, and educator, Storr has had a remarkable influence on the art world. Yet, when painting, Storr prefers not to place his work within the realm of art history. For Storr, his painting practice is more of a respite from the turmoil of the world, than an attempt to place himself within the canon of art. As he notes, “I aim to carve out a space where I can think clearly. It is not a compensation for the chaos—nothing can do that—but it is an alternative. We, humankind, have to correct for imbalances. And so do these pictures.”