Patron is proud to present Long, shore, drift, the gallery’s first solo exhibition with New York–based artist Simon Benjamin. Through a multidisciplinary practice spanning painting, sculpture, installation, printmaking, and video, Benjamin posits the sea and coastal zones as sites of a perennially entangled network of geology and culture. For Benjamin, who is originally from Jamaica, the ecology of the Caribbean becomes a site at which to examine the historical and current relationships between afro-diasporic people and the sea. Emergent from his work to capture his own experiences as an avid surfer and swimmer, Benjamin’s recent work incorporates the physical materials of coastal zones, alongside and in juxtaposition to the visual lexicon of stylized ephemera of tourism produced by an ongoing colonial, commercial economy.

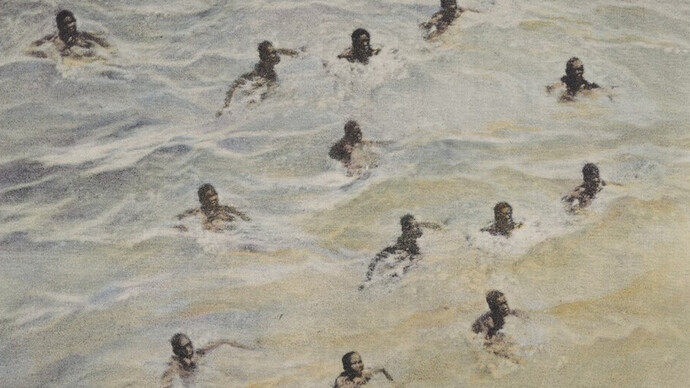

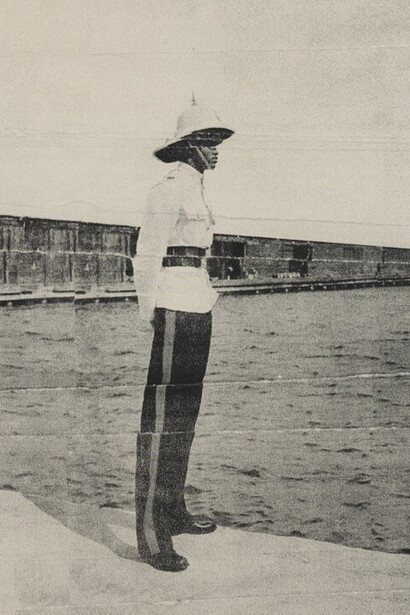

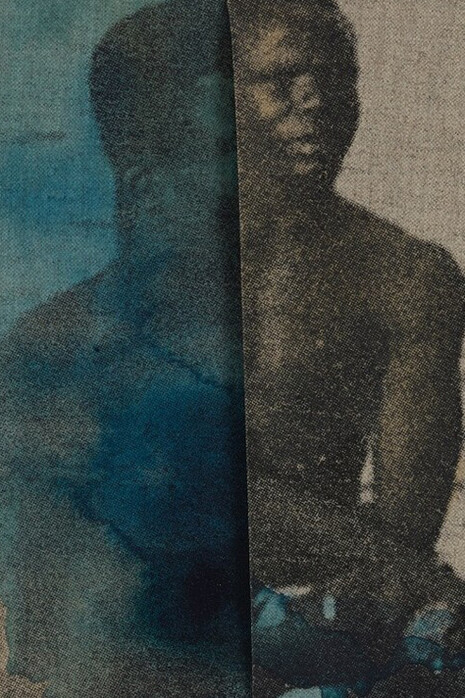

Since 2021, Benjamin has been collecting examples of late 19th-century and early 20th-century travel media, produced in Europe and the U.S. to support Western tourism to Jamaica, the then British-territory. Signifiers of what Krista A. Thompson identifies as the country’s “tropicalization,” the images picture coin divers, young Black men who dived for coins thrown overboard by tourists from incoming steamships in harbors throughout the Caribbean. Tourists cheered on the spectacle, colonial authorities viewed it as a nuisance that undermined their efforts to project an image of order and control of the Black population. The distributed images of scantily clad divers became a popular photographic trope during the early days of the mass tourism industry. Utilizing silkscreens techniques he learned while working in a T-shirt design shop in Kingston, Benjamin transfers the postcard images onto expansive canvases, before hand painting the screen-printed images in washes of jewel-toned blue and green, resisting the serial, mass-produced, imposed imagery. In Port of call no. 5 and no. 6, Benjamin’s source images are stereoscopic slides (widely available in the U.S. and Europe during this era as consumable image media) depicting an assembly gathered a natural rocky outcrop–the British guardsmen’s white uniforms in contrast to the exoticized, nearly nude local men’s bodies. When viewed together, the differences between the two compositions reveal itself, complicating the constructed “vibrancy” of Jamaican life once staged and controlled by the colonial gaze. Embracing the canvas itself as a material rich with seafaring uses, Benjamin’s paintings are at times affixed to wooden structures (themselves echoing types of fish traps continually used in coastal Jamaica), as in Euclides, and folded, as in , compositionally suggesting what cultural theorist Stuart Hall considers as the “hinge between the colonial and the postcolonial lives.”

Collapsing the past, present, and possible futures for those who inhabit, or hold a relation to, coastal regions, Benjamin offers an embodied, physical narrative of the continued impact of colonialism on geological, and cultural ecosystems. The two sculptures in the exhibition, Lenapehoking.NY.2025.06.19.002 and Lenapehoking.NY.2025.06.19.003 take their forms from the geological tool used to study the layers and history of the earth. Assembling found detritus from the shorelines of Brooklyn’s Dead Horse Bay, cornmeal (historically a staple imported into Jamaica as a low-cost food for enslaved people on mono crop plantations), and sand, Benjamin constructs an alternative, partially fictitious record of a coastal site.

Long, shore, drift culminates in a sculptural media installation, Tidalectic no. 1, which combines a monumental core sample created from detritus salvaged from Dead horse bay with a two channel video-installation incorporating footage taken while traveling a glass-bottom boat off Negril, Jamaica. Implicitly gesturing towards the history of oceanic tourism, Benjamin posits his own physical point of view as an embodied participant in not only continuing the use of the sea as a photographic icon of the Caribbean, but documenting a personal experience shared with his loved ones. Captured during the U.S.’s rapid escalation of deep sea mining in the waters of the Caribbean, time collapses around the artist’s gaze, as his own point of view confronts the geological narratives suggested in the core sample and allude to an increasingly precarious future shared by residents of all coastal regions.

Long, shore, drift refers to the geological term longshore drift, a natural process that moves sediment along a coastline resulting from the waves’ repetitive actions. Within the context of the exhibition, the pattern becomes a metaphor for examining how coastlines evolve, a concept Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite’s refers to as tidalectics—a framework that conceives of Caribbean identity as cyclical and fluid, shaped not by fixed geography but by movement and exchange. Continually unfolding and falling back upon itself, Long, shore, drift offers a repetitive, rhythmic reminder of the series of extractions that continue to shape the world and our perception of it.